Then she offered instructions: Steep the mushrooms in a tea and drink it slowly. If you don’t feel anything after 15 minutes, she told my travel partner in Spanish, just eat them. It would be my first-ever psilocybin trip, but given where I’d found myself—how could I not oblige?

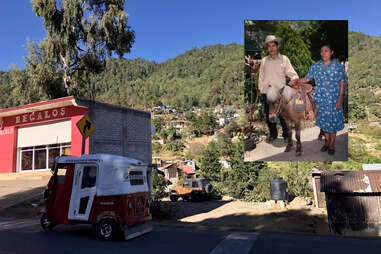

Among the rippling mountains of the Sierra Madre del Sur, San José del Pacifico stands out from its shrubby surroundings with a main drag doused in psychedelic color and toadstool-themed everything. Souvenir stands selling crocheted fungi ornaments and mushroom cap hats line this quarter-mile strip of Highway 175, a route that snakes through the mountains from the high desert all the way to the Pacific Coast. For decades, tourists have stopped here on their way from Oaxaca de Juárez to the bohemian beaches of Mazunte and Puerto Escondido. They come for the Psilocybe mexicana—a species of hallucinogenic mushroom that grows here and in Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Guatemala at elevations above 5,000 feet.

Oaxacans have consumed these mushrooms for their healing properties since ancient times. But in 1957, American scientist and writer Robert Gordon Wasson broadcasted them to the world in “Seeking the Magic Mushroom,” published in Life. His essay drew tourists to another Oaxacan mountain village, Huautla de Jiménez, where a native Mazatec shaman named María Sabina lived. Throughout the ‘60s, psychonauts flooded the area seeking Sabina and spiritual enlightenment. The late curandera (or “female folk healer”) never learned to read, write, or speak Spanish—only her Indigenous language—but continued to bridge the gap between los hongos psicodélicos and foreigners by guiding tourists in psilocybin-fueled ceremonies. It’s even rumored that her clientele included the Beatles, though that’s never been substantiated.

Tourism in Huautla blossomed over the decade following Wasson’s essay, to the dismay of villagers forced to contend with hippies perpetually spilling out of the town’s one and only hotel and onto the banks of the river, where they would reportedly camp. The villagers requested an intervention, and in 1969, the military both deported foreigners and established a checkpoint to keep them from getting back in—one that remained operational until the mid-’70s.

“Even if Huautla was under military siege for almost a decade, this didn't really stop foreigners looking for mushrooms,” says Marcos Garcia de Teresa, a social anthropologist who researches the area’s mushroom trade. “But it may have pushed some of them to look for other places.” Conveniently, a celestial phenomenon not unlike the one that will sweep the US on April 8 came calling from the other side of the mountains.

In March of 1970, travelers from all over North America flocked to Mexico’s Miahuatlán District, where San José del Pacifico sits. They wanted to catch what NASA officials were calling the solar eclipse of the century. Older generations are now passing on the stories of what it was like to be in the path of totality—and of what came after.

Jonathan Ruiz Ramírez, whose family runs Cabañas Los Pinos in San José del Pacifico, grew up hearing stories of that fateful day from his abuelitos, who lived through it. “The few places to eat and stay that existed then were quickly crowded,” he told me. “There were different celebrations to welcome the visitors, who continued to arrive even on the day of the eclipse.” Scientists came from all over the world and set up viewing stations in the mountains around San José del Pacifico. Reports described the atmosphere in villages across the region as carnival-like, with dancing, chanting, the ringing of church bells, and fireworks leading up to the big day.

Ruiz Ramírez’s abuelitos remember that while many of the villagers on the outskirts of town went about their everyday farm chores, others who lived close to the community’s center “joined the visitors who had arrived to appreciate the eclipse carrying fruits, bread, tortillas, and products that they [made] themselves.”

Psychedelic mushrooms and other drugs were made available in addition to the generous food offerings, which helped build San José del Pacifico’s reputation as the new Oaxacan epicenter of counterculture. It didn’t hurt that the area also has the ideal weather for growing marijuana and poppy, unlike the slightly colder Huautla. What’s more, it was the perfect stopping point for those traveling between the city of Oaxaca and the coast. Now a new generation of entrepreneurs are committed to making sure that San José del Pacifico continues to hold onto its credibility with tourists.

These days, companies like Coyote Aventuras offer retreats to San José del Pacifico from Oaxaca. Owner Carlos Hernández first tried mushrooms there 20 years ago with a villager who started dosing with psilocybin when he was only eight. Hernández told me that while the 1970 solar eclipse catalyzed tourism in the region, interest in psychedelics has grown substantially even in the past decade. What he calls a “huge wave of spiritual tourism” seems backed up by data: Trend reports from the Global Wellness Institute and Research and Markets show that the worldwide markets for both psychedelics and "wellness tourism" are slated to double to $10.8 billion and $1.4 trillion, respectively, from 2020 to 2027.

Visitors can find drugs almost anywhere in San José del Pacifico, be it at a souvenir shop like the one where I found mine, or a temezcal—a traditional sweat lodge where local healers guide psilocybin-infused ceremonies like the ones Sabina once held. Although he hasn’t worked mushroom tripping into his tour itinerary yet, Hernández said his team offers information, transportation, accommodation, lunch, some guidance, hiking, yoga, and more to those who want to try it. In the meantime, tourists can stay in hostels whose dorm rooms are named after mushroom species, visit a bus station serving a company aptly called “Eclipse 70,” and dine at cafes with trippy murals on the walls.

Hernández noted that psilocybin mushrooms are, in fact, illegal throughout Mexico, but the penal code exempts them where “it can be presumed that they will be used in the ceremonies, uses, and customs of Indigenous peoples and communities, as recognized by their own authorities.” The mushrooms are anything but clandestine in San José del Pacifico, where, in the high season, kids can be found selling them on the side of the road.